BOOK THIS SPACE FOR AD

ARTICLE ADCrowdsourced security was a key tool in securing some countries’ efforts, while others missed the mark

As the Covid-19 pandemic began spreading across the globe in 2020, governments worldwide raced to develop tracking apps to help contain the virus.

The list of countries with track and trace apps is exhaustive, with the UK, France, India, Australia, China, and Hong Kong just some of those included.

But as is often the case, the rush to push projects out in a short amount of time came at the expense of user security and privacy.

Read more of the latest news about bug bounty programs

Notable issues, of those that have been publicly reported, include major privacy holes and the leaking of sensitive data in some cases.

As a result, last year saw the launch of a number of bug bounty programs and vulnerability disclosure programs (VDPs) specifically designed to secure track and trace applications.

Securing the world

The World Health Organization (WHO) launched its VDP in conjunction with HackerOne in December 2020, asking white hats to look for flaws in its mobile app.

It was one of the first high profile programs to be announced and, to date, has resulted in the patching of seven security vulnerabilities uncovered by ethical hackers.

HackerOne also worked with the UK’s Department of Health and Social Care to launch a VDP for the NHS track and trace app and its supporting infrastructure.

A number of “wide ranging” security flaws were reported during a pilot test of the app, according to a report from Australian security researchers Dr Chris Culnane and Vanessa Teague.

These security failings, as detailed in this blog post, included various TLS server implementation issues that could lead to the leaking of unencrypted data, spoofing false positive test results, and other issues.

The UK’s signals intelligence agency GCHQ said all security and privacy issues were fixed prior to the national rollout of the app.

BACKGROUND Contact tracing bug bounty: France’s StopCovid project launches public program

Across the channel, the French government employed European bug bounty platform YesWeHack to run its bug bounty program for tracing app StopCovid.

In contrast to other government-funded programs, which are unpaid VDPs, white hat hackers are offered monetary awards up to €2,000 (around $2,300) for critical vulnerabilities (as well as a free t-shirt) under this scheme.

The program has so far confirmed 35 reports, though in response to questions from The Daily Swig, the French National Agency for the Security of Information Systems (ANSSI) declined to give any detail on the types of bugs uncovered.

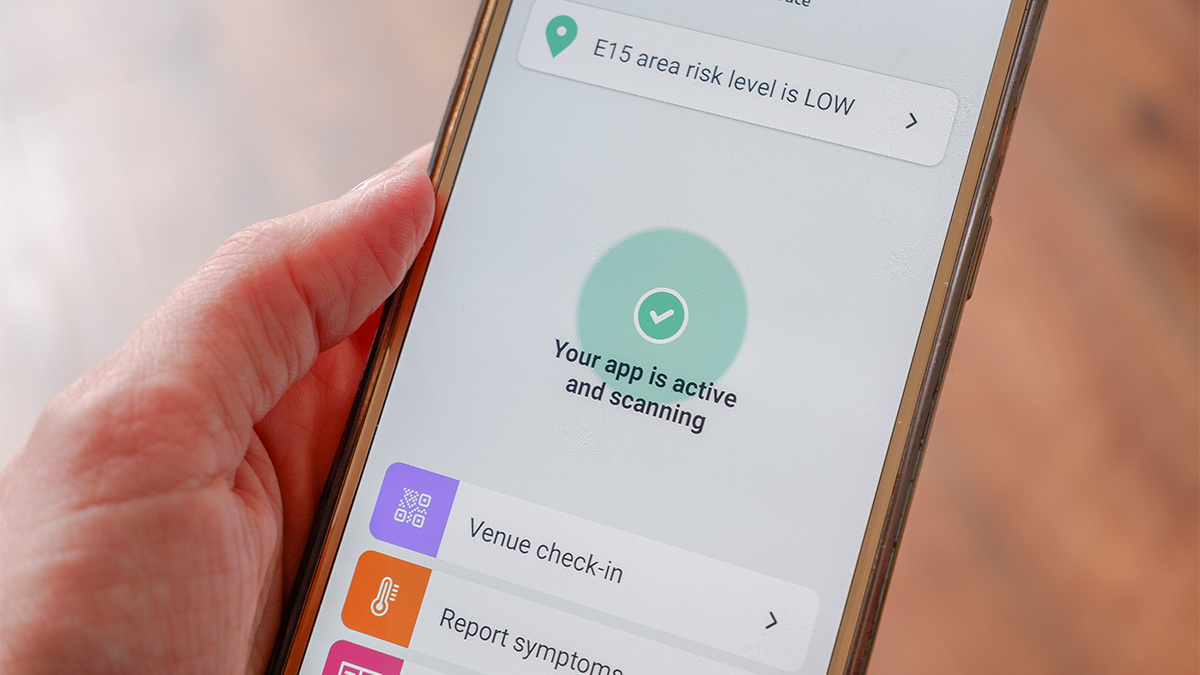

A screenshot of the NHS track and trace app

A screenshot of the NHS track and trace app

Mandatory privacy risk

While many government-funded tracing apps were somewhat optional (venues could request the use of the app before entry at their discretion), in India it was mandatory. Indian citizens couldn’t ride a bus, for example, without checking into the app.

Making the app compulsory was initially a move designed to protect Indian citizens from exposure to disease, though combined with a raft of major security holes, it also left them vulnerable to other risks.

Baptiste Robert, a French security researcher known online as Elliot Alderson, whose extensive experience testing Indian websites and apps has earned him a reputation across India, was one of the first to report issues with India’s Aarogtu Setu app.

RELATED The age of Covid-19: Lockdowns and cybersecurity, 12 months on

The contract tracing application was launched in April 2020, bringing with it major privacy blunders, as Robert discovered.

The app allowed users to view how many people were infected within a limited radius, however Robert was able to subvert this functionality and use it to put a microscope on what was happening at specific locations.

Robert proved his concept by combining the two security flaws to pinpoint the number of infected people within India’s prime minister’s office.

‘A lot of issues’

Robert told The Daily Swig that there was no bug bounty program for the app when it launched, and that he was only able to conduct his research due to a good relationship with India’s government.

“For, let’s say, ‘normal people’, it can be super complicated to disclose something [without a bug bounty program], especially in India. You can have a lot of issues, but for me it was okay.”

Robert said he pushed the government to create a bug bounty program, instead it decided to make the application open source – though even this move drew criticism due to the fact that its codebase wasn’t actually publicly available in full.

The researcher said: “I tried to push the Indian government to open source their application and say, okay, this is something people have the right to know, what is inside the Aarogaya Setu app. So they decided to open source the application, but in reality, it was not really open source.”

A report from the Internet Freedom Foundation noted that GitHub users “have commented that the source code provided on the official GitHub release does not match the actual version of the app, which is available for the users to download and use”.

“In other words, the researchers and developers cannot contribute to the process because they have not even been given the actual code to work with!”

Demonstrating trust

So far in 2021, the Indian government has not yet fully open sourced the app. But in other countries, small wins can be found in their attitude towards crowdsourced security.

Commenting on bug bounty programs, a spokesperson from YesWeHack told The Daily Swig:“Governments need to protect citizens’ data in order to minimize the risk of malicious acts, and bug bounty allows real in-depth security – bug bounty [programs] allow [researchers] to confront an application in real conditions, with different approaches and methodologies.”

They added: “Users are today arguing strongly for transparency and security from digital players and governments and having your application tested by thousands of researchers demonstrates your transparency and respect for your users.”

YOU MAY LIKE Microsoft Teams is the first target for new app-focused bug bounty program

.png)

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·