BOOK THIS SPACE FOR AD

ARTICLE ADWith many in the public sphere warning about a potential compromise of the integrity of the Presidential Election, security researchers instead flag online resources and influence campaigns as the biggest problem areas.

With the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election coming up in just two months and change, cybersecurity concerns have come to the fore for average citizens and politicians alike. That said, the likelihood of election results being impacted by an attack is pretty slim, according to security researchers. Instead, there’s a myriad of other at-risk election infrastructure that everyone should be paying attention to.

When it comes to election security, worries about the integrity of voting machines often pop to mind, and the expected expansion of mail-in voting due to COVID-19 has also sparked concerns. Past direct hacking efforts, such as the attack on the Democratic National Committee in 2016, have left many nervous that this time around, the actual election results could be compromised in some way.

The worry that someone could change or delete election results directly is a bit of a tempest in a teapot, according to researchers.

“Most voting machines in use today, from the well-known market leaders, are ‘reasonably’ secure from cyberattacks due to the fact that the terminals are typically air-gapped from any connected network during the individual voting process,” Bill Rials, associate director and professor of practice of the Tulane University School of Professional Advancement Information Technology Program, told Threatpost. “Any vote cast is usually stored locally and not transferred over a network until after the polls close and the tabulation occurs. From a cybersecurity perspective, the biggest risk to elections is all the ancillary elements associated with the election process.”

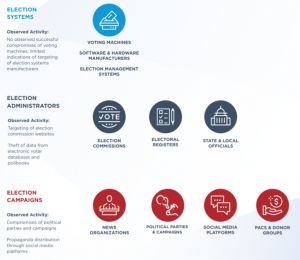

Those ancillary elements include the availability of state and local voter registration websites and other support infrastructure, safeguarding campaigns’ sensitive data and thwarting nation-state-backed influence campaigns.

“We saw with the U.S. presidential cycle in 2016 that there were some attempts to potentially gain some access into election voting systems themselves and ballot systems, but the biggest impact we saw was the targeting of campaigns, the targeting of candidates, and not just specifically of the parties but also ancillary groups surrounding those candidates and parties,” said Ron Bushar, SVP and CTO, Government Solutions Consulting at Mandiant, speaking at the recent FireEye Virtual Summit. “Those hacking efforts, especially if they’re timed properly, can really have devastating effects on the perception of a voting system by the people participating in that election.”

Voting systems themselves usually have double- or triple-redundancy when it comes to the election returns.

“Many states mandate that paper ballots have to be maintained, and you have usually two or three different copies of the electronic results physically stored within the systems,” Bushar said. “And then of course, you have the digital copies that are that are sent out. And in every instance, the certification of those votes has to be done through a manual process, even after initial results are in. So from our perspective, while those obviously are the most important systems in the voting ecosystem, and they’re certainly targeted, it’s very, very difficult to impact the outcome of an election by hacking the results.”

Meanwhile, recent stats from the Black Hat USA 2020 Attendee Survey show that 85 percent of respondents believe that cyber-threat actors will have at least some impact on the U.S. elections in 2020. And disturbingly, nearly one third of respondents believe that the impact will be critical, and that the results of the 2020 election will always be in doubt as a result.

Targeting Election Resources

One of the weak links to be concerned about is the availability of the online resources that help citizens to register to vote, find polling locations or learn more about candidates, according to recent statistics — as well as the IT systems used by state and local offices. Problems in this arena can be more impactful than it would seem on the surface, especially when it comes to securing the voter rolls to prevent tampering and voter suppression.

“Due to the spread of COVID-19, we are seeing a number of election environments shift online, to varying degrees, with political parties conducting virtual fundraisers, campaigns moving town halls to online platforms and election officials using online forms to facilitate voting by mail,” said Jocelyn Woolbright, a researcher with Cloudflare, who added that cybercriminals are increasingly targeting these resources.

From April to June, Cloudflare saw a trend of increasing DDoS attacks against political campaigns, with double the number attacks observed in its telemetry compared to the first three months of 2020. Overall, political campaigns have been experiencing an average of 4,949 cyber-threats per day, although larger campaigns are seeing many more than that, according to the analysis. This is problematic given that campaigns now rely on online platforms like videoconferencing, online fundraising and social media to reach voters.

“When looking at the ecosystem of election security, political campaigns can be soft targets for cyberattacks due to the inability to dedicate resources to sophisticated cybersecurity protections,” Woolbright said. “Campaigns are typically short-term, cash strapped operations that do not have an IT staff or budget necessary to promote long-term security strategies.”

For state and local governments, constituents are accessing online information about voting processes and polling stations in noticeably larger numbers of late – Cloudflare said that it has seen increases in traffic ranging from two to three times the normal volume of requests since April. So perhaps it’s no coincidence that the firm found that government election-related sites are experiencing more attempts to exploit security vulnerabilities, with 122,475 such threats coming in per day (including an average of 199 SQL injection attempts per day bent on harvesting information from site visitors).

“We believe there are a wide range of factors for traffic spikes including, but not limited to, states expanding vote-by-mail initiatives and voter registration deadlines due to emergency orders by 53 states and territories throughout the United States,” Woolbright said.

Mandiant’s Bushar added that cyberattackers have also been targeting the IT infrastructure used by commissions and the boards of election, and the enterprise computer systems, email and other back-office gear that’s used both at the state and the county/local levels for the administration of elections. One primary concern on this front is securing the availability and integrity of the voter registration databases on election day.

Tulane’s Rials noted that these voter registration databases are typically stored and maintained by county clerks and election commissioners.

“These databases are susceptible to cyberthreats, just like any other database,” he noted. “Unfortunately, many local governments are still struggling to increase their cyber-defense capabilities and are easy targets. Cybercriminals wishing to disrupt the election process are likely targeting these voter-registration databases months and even years leading up to election day. Incorrect or modified voter data could have an impact on the election process. Local governments who are responsible for the cyber-protection of these databases should be working now to improve the cybersecurity posture associated with the voter databases.”

In terms of best practices for thwarting these kinds of attacks, there are foundational efforts for what an organization can do, starting with establishing a written information-security program and incident-response plan, according to Ben Woolsey, manager at Mandiant.

“Not only should they have a systematic approach to how to handle an incident, but how to specifically handle specific incidents based on intelligence about what threats are out there,” he noted, during the FireEye Virtual Summit. “Then, have you practiced that? Training as an exercise is extremely important.”

Organizations should also take periodic health checks leading up to the up to the day of the election, with enhanced hunting and monitoring efforts kicking in two weeks out, he noted.

“Not just hunting for simple signatures and hash values but looking for evidence of the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used by nation-state adversaries and other major groups,” Woolsey said.

And finally, on the day of the election, organizations should have a war room, whether virtual or on-premise, populated with a designated executive in charge, malware analysts and incident-response specialists — in case attackers try to mount a DDoS or ransomware attack on campaigns or election infrastructure — or worse.

“The dream of the war room is to have one of the most boring days of your life,” Woolsey said. “You come in early in the morning, you sit there, nothing happens. And then the war room gets stood down after the after the vote is counted. That’s the ideal War Room scenario.”

Organizations may get outside help too: Christopher Krebs, director of the Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency (CISA), said at Information Security Media Group’s Cybersecurity Virtual Summit recently that the Feds will offer local and state government election officials technical support, training and cyber-hygiene exercises needed to ensure a more secure election in November. Also, the U.S. government is offering a reward of up to $10 million for anyone providing information that could lead to tracking down potential cybercriminals aiming to meddle in the November contest.

Nation-State Actors and Social Influence

State-sponsored cyberattackers continue to be a bugbear for election security. But while direct hacking activity remains a concern, nation-state meddling is more likely to take the form of spreading divisiveness and disinformation — mainly through online social-media bots and troll farms.

“In the midterm elections, the only thing we observed was disinformation and social-media manipulation; there was very little targeting of other components, and there was no major hacking and leaking of candidates or campaigns or parties,” Bushar said, adding that such activity has been minimal in 2020 as well. “But as to what’s going to happen this this go around, it’s hard to say.”

In the Black Hat attendee survey, more than 70 percent said influence campaigns will have the greatest impact on the elections. As keynote speaker Renée DiResta, research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, detailed at the show, the anatomy of these attacks has become somewhat standard. There is first the creation of thousands of fake-personae accounts. Then there’s the development of content, which is seeded to social platforms. Next, dubious news sites generate plausible — yet bogus — articles that amplify a core message. If successful, the viral nature of the “news” piques the interest of mass-media news sites. They take the bait and report on the viral “news” as fact.

“It gets really challenging to try to discern between legitimate speech, political speech and what becomes fake news or amplification of fake news,” Bushar said. “Espionage and traditional data theft is certainly also a play here, especially on the candidates and the parties. That’s either for purposes of understanding how to mount a social-media disinformation campaign, or to take pieces of legitimate information that were stolen, combine that with other fake news or false information, and create a powerful narrative that can really gain traction – that’s hard to counter.”

When it comes to the adversaries involved, about 69 percent of Black Hat survey respondents said they expect disinformation efforts to emanate primarily from Russia.

“One of Russia’s key goals is to further deepen divides in the population, whether that is with Brexit in the UK or with gun control or Black Lives Matter in the U.S.,” said Duncan Hodges, senior lecturer in Cyberspace Operations at the U.K.’s Cranfield University, via email. “For them, it is little effort, so any gain is beneficial and helps weaken the West, E.U. and NATO, this not only structurally benefits Russia but is important for the domestic population at home in Russia.”

Russia isn’t alone in mounting influence campaigns, however: China, Iran and others have also put considerable resources into such efforts.

“Beyond the Russia threat, which has been fairly well-documented, there are multiple examples of Chinese cyberespionage [in service to influence campaigns],” Bushar said. “Iran has a less direct focus on individual election campaigns, but they’re very, very active in the false persona disinformation, and are especially very active on platforms such as Facebook. They create hundreds or thousands of fake accounts and really amplify news stories that are obviously pro-Iranian. We haven’t seen them targeting any specific elections systems or election infrastructure yet.”

Many times, these influence campaigns are highly targeted. For instance, researchers at GroupSense recently found evidence that foreign actors are preparing to target Native Americans for the 2020 election.

“They’re currently setting up troll accounts on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and building a base of followers to prepare for future disinformation campaigns,” Kurtis Minder, CEO of GroupSense, said via email. “Some of the states with the largest Native American populations are also battleground states: Arizona, Michigan, North Carolina, Florida, Texas and Wisconsin. And, as we saw in Michigan, where the vote differential was 11,000 in 2016, it doesn’t take much to tip a close election (there are 50,000 Native Americans in Michigan, by the way).”

Social-media giants have worked to reduce the ability of nation-state actors to user their platforms for these campaigns: Twitter in June in fact took down three separate nation-sponsored influence operations, attributed to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Russia and Turkey. Collectively the operations consisted of 32,242 bogus or bot accounts generating the content and various amplifier accounts that retweeted it. However, more needs to be done.

“We have to coordinate on the identification of fake accounts,” Mandiant’s Bushar said. “False personas, false news stories, there has to be a partnership of government intelligence-sharing with critical infrastructure providers and state and local governments to make sure they have all the visibility they can possibly get to defend against these threats.”

It’s the age of remote working, and businesses are facing new and bigger cyber-risks – whether it’s collaboration platforms in the crosshairs, evolving insider threats or issues with locking down a much broader footprint. Find out how to address these new cybersecurity realities with our complimentary Threatpost eBook, 2020 in Security: Four Stories from the New Threat Landscape, presented in conjunction with Forcepoint. We redefine “secure” in a work-from-home world and offer compelling real-world best practices. Click here to download our eBook now.

.png)

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·