BOOK THIS SPACE FOR AD

ARTICLE ADRecently, our anti-virus laboratory discovered an interesting new modification of a file virus known as Expiro which targets 64-bit files for infection. File-infecting viruses are well known and have been studied comprehensively over the years, but malicious code of this type almost invariably aimed to modify 32-bit files. One such family of file viruses, called Expiro (Xpiro), was discovered a long time ago and it’s not surprising to see it today. However, the body of this versatile new modification is surprising because it’s fully cross-platform, able to infect 32-bit and 64-bit files (also, 64-bit files can be infected by an infected 32-bit file). According to our naming system the virus is called Win64/Expiro.A (aka W64.Xpiro or W64/Expiro-A). In the case of infected 32-bit files, this modification is detected as Win32/Expiro.NBF.

The virus aims to maximize profit and infects executable files on local, removable and network drives. As for the payload, this malware installs extensions for the Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox browsers. The malware also steals stored certificates and passwords from Internet Explorer, Microsoft Outlook, and from the FTP client FileZilla. Browser extensions are used to redirect the user to a malicious URL, as well as to hijack confidential information, such as account credentials or information about online banking. The virus disables some services on the compromised computer, including Windows Defender and Security Center (Windows Security Center), and can also terminate processes. Our colleagues from Symantec have also written about the most recent Expiro modification. TrendMicro also reported attacks using this virus.

The Win64/Expiro infector

The body of the virus in a 64-bit infected file is added to the end of the new section of the executable file, called .vmp0 with a size of 512,000 bytes (on disk). To transfer control to the main body (.vmp0), the virus inserts 1,269 bytes of malicious startup code in place of the entry point. Before modifying the entry point code, the virus copies the original bytes to the beginning of the .vmp0 section. This startup code performs unpacking of the virus code into the .vmp0 section. In the screenshot below we show the template for the startup code to be written during infection to the entry point of the 64-bit file.

During the infection process, the virus will prepare this startup code for insertion into the specified file and some of these instructions will be overwritten, thus ensuring the uniqueness of the .vmp0 section contents (polymorphism). In this case, the following types of instruction are subject to change: add, mov, or lea (Load Effective Address), instructions that involve direct offsets (immediate). At the end of the code, the virus adds a jump instruction which leads to the code unpacked into the .vmp0 section. The screenshot below shows the startup code pattern (on the left) and startup code which was written into the infected file (on the right).

Similar startup code for 32-bit files is also located in the section .vmp0 as presented below.

This code in x32 disassembler looks like usual code (infected file).

The size of the startup code in the case of a 64-bit file is equal to 1,269 bytes, and for an x32 file is 711 bytes.

The virus infects executable files, passing through the directories recursively, infecting executable file by creating a special .vir file in which the malicious code creates new file contents, and then writes it to the specified file in blocks of 64K. If the virus can’t open the file with read/write access, it tries to change the security descriptor of the file and information about its owner.

The virus also infects signed executable files. After infection files are no longer signed, as the virus writes its body after the last section, where the overlay with a digital signature is located. In addition, the virus adjusts the value of the field Security Directory in the Data Directory by setting the fields RVA and Size to 0. Accordingly, such a file can also be executed subsequently without reference to any information about digital signatures. The figure below shows the differences between the original/unmodified and the infected 64-bit file, where the original is equipped with a digital signature. On the left, in the modified version, we can see that the place where the overlay shown on the right was formerly located is now the beginning of section .vmp0.

From the point of view of process termination, Expiro is not innovative and uses an approach based on retrieving a list of processes, using API CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, and subsequent termination via OpenProcess / TerminateProcess. Expiro targets the following processes for termination: «MSASCui.exe», «msseces.exe» and «Tcpview.exe».

When first installed on a system, Expiro creates two mutexes named «gazavat».

In addition, the presence of the infector process can be identified in the system by the large numbers of I/O operations and high volumes of read/written bytes. Since the virus needs to see all files on the system, the infection process can take a long time, which is also a symptom of the presence of suspicious code in the system. The screenshot below shows the statistics relating to the infector process at work.

The virus code uses obfuscation during the transfer of offsets and other variables into the API. For example, the following code uses arithmetic obfuscation while passing an argument SERVICE_CONTROL_STOP (0x1) to advapi32!ControlService, using it to disable the service.

With this code Expiro tries to disable the following services: wscsvc (Windows Security Center), windefend (Windows Defender Service), MsMpSvc (Microsoft Antimalware Service, part of Microsoft Security Essentials), and NisSrv (Network Inspection Service used by MSE).

Win64/Expiro payload

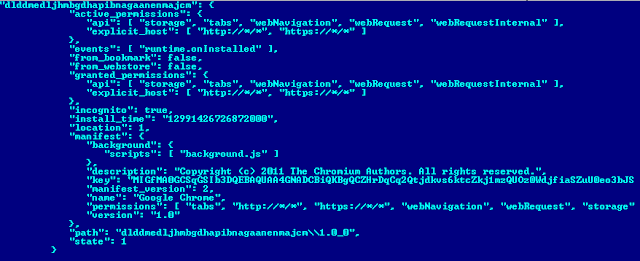

As the payload, the virus installs a browser extension for Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox. The manifest file for the installed Chrome extension looks like this:

In the Chrome extensions directory, the directory with malicious content will be called dlddmedljhmbgdhapibnagaanenmajcm. The malicious extension uses two JavaScript scripts for it work: background.js and content.js. After deobfuscation, the code pattern of background.js looks like this.

The variable HID is used for storing the OS version string and Product ID. The variable SLST is used to store a list of domains that are used to redirect the user to malicious resources.

The manifest file for the Firefox extension looks like this:

In the screenshot below you can see part of the code of content.js which performs parsing of form-elements on the web-page. Such an operation will help malicious code to retrieve data that has been entered by the user into forms, and may include confidential information.

As a bot, the malware can perform the following actions:

change control server URLs;execute a shell command – passes it as param to cmd.exe and returns result to server;download and execute plugins from internet;download a file from internet and save it as %commonapddata%\%variable%.exe;implement a TCP flood DoS attack;enumerate files matching mask \b*.dll in the %commonappdata% folder, loading each one as a library, calling export «I» from it, and loading exports «B» and «C» from it;start proxy server (SOCKS, HTTP);set port forwarding for TCP on the local router (SOAP).Expiro tries to steal FTP credentials from the FileZilla tool by loading info from %appdata%\FileZilla\sitemanager.xml. Internet Explorer is also affected by Expiro which uses a COM object to control and steal data. If a credit card form is present on a loaded web page, malware will try to steal data from it. The malicious code checks form input data for matches to «VISA» / «MasterCard» card number format and shows a fake window with message:

“Unable to authorize.\n %s processing center is unable to authorize your card %s.\nMake corrections and try again.”

This malware can also steal stored certificates with associated private keys (certificate store «MY»).

Implications of Win64/Expiro

Infecting executable files is a very efficient vector for the propagation of malicious code.

The Expiro modification described here represents a valid threat both to home users and to company employees. Because the virus infects files on local disks, removable devices and network drives, it may grow to similar proportions as the Conficker worm, which is still reported on daily basis. In the case of Expiro the situation is getting worse, because if a system is left with at least one infected file on it which is executed, the process of total reinfection of the entire disk will begin again.

In terms of delivery of the payload, the file infector is also an attractive option for cyber crime, because viral malicious code can spread very fast. And of course, a cross-platform infection mechanism makes the range of potential victims almost universal.

Big hat tip to Miroslav Babis for the additional analysis of this threat.

.png)

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·